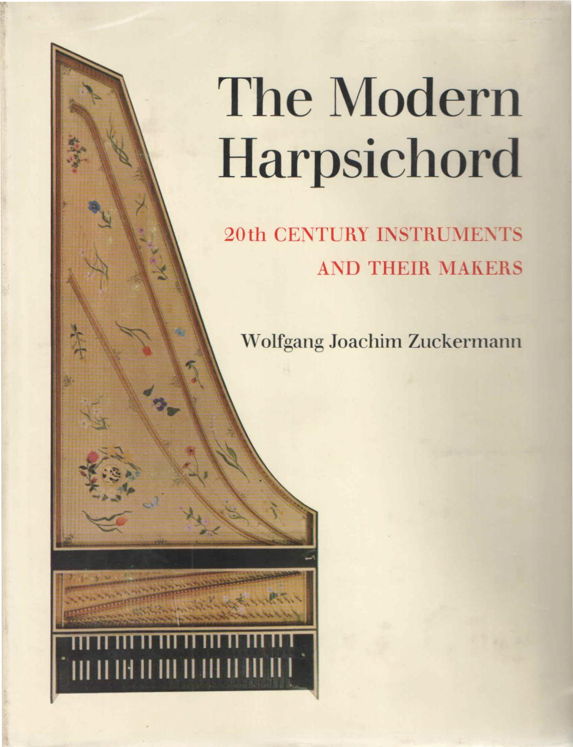

The Modern Harpsichord:

a tribute to Wolfgang "Wally" Zuckermann (1922-2018)

Wolfgang Joachim Zuckermann (so named in honor of Mozart and Goethe) was born in Berlin on October 11, 1922. His family fled Nazi Germany in 1938 and settled in Manhattan, where his father opened a leather goods factory. He served with the 10th Armored Division of the United States Army in France and Germany during World War II, and in 1949 earned a B.A. degree in English and psychology at Queens College in New York. He worked for a while as a child psychologist, but abandoned the field to study piano mechanics at a trade school, reasoning that it was easier to repair a keyboard instrument than a damaged psyche. Although he had been a cellist since childhood, his love of Baroque chamber music, coupled with expertise in keyboard technology, kindled his interest in the harpsichord. He built his first instrument in 1955 during an era of revived popularity of Baroque music when there were few harpsichord makers in the United States, and responding to market demand, established himself as a commercial harpsichord builder. By 1960 he had sold approximately seventy instruments, but found himself overwhelmed by service calls, as his clients were reluctant to perform routine maintenance themselves. Assuming that harpsichord owners would be less intimidated if they built their own instruments, he developed an affordable DIY kit that became extremely popular, selling over 10,000 units by 1969. That same year, Zuckermann published The Modern Harpsichord, a critical survey of contemporary harpsichord makers around the world.

I read The Modern Harpsichord when I was in high school, my interest in Baroque music having been piqued by Walter Carlos's Switched on Bach record album. The book ignited a passionate desire to own a harpsichord, even though I wasn't a keyboard player and I lacked even the most rudimentary mechanical skills that assembling the Zuckermann kit would have required. Needless to say, my parents nixed the idea (although I did acquire a 5-octave upright piano during my senior year of high school, admittedly a more practical alternative). This composition, a derangement based upon François Couperin's Tic-toc-choc (Pièces de clavecin, 3e livre, no. 18) is what my Zuckermann harpsichord might have sounded like had I ever succeeded in building one.